Not lifting a finger: the lazy whistler's guide to fingering

Introduction

As I keep saying, I'm lazy by nature. I believe in efficiency and economy of movement. This means I prefer not to lift fingers unnecessarily. And with a little trial and error you'll soon find that it is very possible to lift lots of fingers unnecessarily when playing the whistle!

High D (second octave)

The point I am going to make here regarding the fingering of high D is very basic. It might seem so obvious that you may wonder why I am bothering to make it at all. The answer is that I quite often come across student players who have been at the whistle for quite some time and have not figured this one out, to the detriment of their playing.

Look at just about any fingering chart for the whistle and you'll notice that the fingering given for high D indicates that the first tone hole (under the B finger, the first finger of the top hand) should be left open. This is all well and good. Opening this hole gives a good clear sound, and incidentally makes it impossible to sound the low D.

But I don't understand why most of these fingering charts don't point out that you can just as easily play the same note with all the fingers down, by overblowing. And in many passages, it makes much more sense to leave this finger down. If you always lift the first finger to play high D, just try this exercise:

To change from B to D using this "standard" fingering involves doing what I call a complete oil-change - you have to change the position of all your fingers. See how fast you can play this passage cleanly in this way. Now try the same passage, but leaving your B finger down. I'll be willing to bet you can easily play the passage much much faster. Now, you'll say, what tune that I'd want to play has a passage like that in it? It's just to illustrate a point. (I could probably dig up some passages from real-world tunes that would equally problematical, except that just now I'm too lazy.)

Similarly (or should that be conversely?), there are many passages where it makes no sense at all to put the B finger down to play high D, particularly passages involving moving from C# or C-nat to high D and back again. So get into the habit of using the fingering that suits the passage in the tune you are playing. You may want to use the "standard" (nonlazy, B-finger off) fingering to get the clearest possible sound when you are playing a slow tune, or to sound the last note in the tune that ends on high D. In all other situations, let convenience and common sense decide for you.

C-sharp (and B. And maybe A)

Back to our fingering charts. They will tell you that to play C#, you need to lift all your fingers off the whistle. You will quickly notice that doing so induces fear of dropping your whistle! (Discussed under the topic Relax!)

Fortunately, as the fingering charts may point out, or as you have probably read or been told, there is a way to allay this fear. As you play C# you can keep your 6th finger (ring finger of your bottom hand) on its hole to stabilize the whistle. This will not affect the pitch of the note.

As we just said, covering the lowest tone hole does not affect the pitch of C#. But actually, you can put down all three fingers of your bottom hand, and your C# will still ring out clear and true. Try it.

This is a highly useful thing to know. It means for example, that you can play high d-c#-d by moving only two fingers - instead of five or six. Like this.

- Play a high d with your first finger lifted [|oxx-xxx].

- Now lift fingers 2 and 3 [|ooo-xxx] for c#.

- Stick 'em back on for the again for the next d.

This is the art of not lifting a finger!

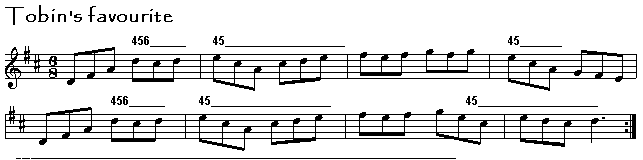

Let's look at that last sequence in the context of a tune. Below are the first eight bars of Tobin's favourite.

The numbers above the staff indicate which fingers you don't need to lift. For instance, the "456" in the first bar means that you can leave the three fingers of your bottom hand in place for the notes covered by the horizontal line - the d-c#-d sequence we have just discussed.

But wait. It gets better still. If you're really lazy, you can try leaving fingers 4 and 5 down for the whole of the next bar. Government pitch warning: This will probably make your A a little flat, so if you're playing unusually slowly, or if you have perfect pitch, or if you are very particular about pitch, you might not like the effect. (Although in general, people with perfect pitch do not take up the tin whistle!)

The same caveat about the flattened A applies to the next indication, over bar 4. You might wish to keep fingers 4&5 down only for the first two notes of the sequence.

However, in the last example, in bars 7 & 8, you can safely keep fingers 4&5 down the whole time.

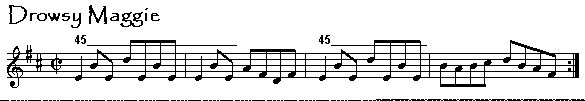

Here's another example, Drowsy Maggie. This does not actually involve C#, but B. As with c#, we can leave fingers 4, 5 and 6 down without affecting the pitch of the note B.

The first time you attempted this popular tune, you may have found it a bit of a finger-twister. Well, try following the indications above, and leave fingers 4 and 5 down throughout the whole E-B-d "rocking pedal" sequence. I think you'll find it a lot simpler. You only have to move the fingers of one hand at a time. You can also, of course, leave finger 1 down for the whole sequence, further restricting the amount of digital gymnastics necessary.

Am I convincing you of the virtues of laziness?

C-natural

I'd really rather leave the whole question of C-natural alone! But I suppose I'll have to say something about it, so here goes. There are three main ways to play C-natural (in the first octave).

- You can play the full, two-handed cross-fingering, which we can also call a "piper's C", or forked" fingering. Like this: [|oxx-xox].

This is my preferred fingering, and gives the truest C-natural on the kind of whistles I like. Unfortunately, on some modern, louder whistles, this pattern gives a note that is far too flat. They are tuned for the next cross-fingering:

- One-handed cross-fingering: [|oxx-ooo]

This works well on the new-fangled whistles I mentioned in the last point. For those of us playing whistles that behave more conventionally, this fingering gives us an opportunity to be lazy. I use this fingering for fast and tricky passages (examples below).

- You can half-hole the C-natural: cover approximately half the C# hole (which is the top hole, or the one covered by your B finger!) to produce a C-natural.

In the second octave, the cross-fingering most likely will not work.

-

The first fingering to try for the second-octave C-natural is: [|oxo-ooo].

This works well enough on conventional whistles. It may not work on the louder models. In which case, ask the maker what you are supposed to do!

- Half-holing works just the same in the second octave as in the first. I find I use it, proportionally, much more often in the second octave, often because this top C-natural is the highest note in the tune, and sliding up into it gives a nice effect.

Coming soon: some exercises to test your C-natural skills!

High B

There's really nothing to say about high B. Except that, if you are ornamenting the note (playing cuts and rolls on the high B), you'll probably find it useful to use the same technique as when playing C# - leaving finger 6 down to provide a counterbalance.

Now, if you have a nonstandard whistle - one of these louder models, or some varieties of low whistle - you might get a horrible surprise if you use this technique. Leaving finger 6 down may flatten your high B, or it may cause the note to squawk. You have two solutions: get a quieter whistle or use the little finger of your bottom hand as a stabilizer.

Next page: Twiddly bits ("ornaments")

Previous page: Where do I breathe?

Site contents: Back to the home page

Updated: 20 August 2001